What would happen if Tests in Bradman’s era were five days in length and only 90 overs bowled per day.

Let’s start with a disclaimer: I regard Don Bradman as a genuinely great batsman – one of the top three or four in his own epoch, even, arguably, if forced to make a choice, the number one across his era, though plenty would opt for George Headley. I also regard Bradman as one of the top dozen or so batsmen to have played Test cricket for Australia.

Not rating him one of our top half-dozen one day batsmen does not make me a Bradman hater, but merely reflects the obvious fact that he never played one-dayers. For what it’s worth, I have no doubt that had Bradman played in the 21st century, he would have been every bit as successful at one day cricket as players of the ilk of Virat Kohli, AB de Villiers, Babar Azam, Ricky Ponting or Steve Smith, just to name a few.

One of the things that would have enabled Bradman to succeed in the aforementioned 21st century pyjama game was his scoring speed (albeit on flat featherbeds truly unfairly loaded against bowlers), which was comfortably ahead of the large majority of his contemporaries. His strike rate in Ashes cricket has been accurately estimated at about 58 runs per 100 balls faced. Stan McCabe’s was low 50s, Jack Hobbs’ (most of whose career preceded Bradman’s) mid-40s. Victor Trumper’s was high 60s, daylight ahead of all of his contemporaries except, presumably, Gilbert Jessop.

English cricketer Gilbert L Jessop. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Bradman’s phenomenally prolific batting could perhaps be likened to a motorist on a well-sealed highway: he could go along at a certain relatively high speed safely, but any motorist who tries to increase their speed to unsafe levels will crash sooner rather than later – this can be likened to a top-level batsman reaching 100 on a road, then lifting the tempo before holing out 20 or 25 runs later (or so). The motorist metaphor is a batsman scoring 100 glorious runs off 165 deliveries, and then teeing off for a flurry of boundaries (4.44.6..1.6) then being dismissed attempting increasingly wild shots to finish an ultimately match-winning innings of 125 off 176 balls, an outstanding overall strike rate of 71.0, broken down into 60 for his first 100 runs, followed by 250 for his subsequent final ten deliveries, not counting the 176th that ultimately dismissed him.

Steve Waugh once said that the easiest runs you will ever score are those after 150… I would actually lower this to about 125, but either way, the very credible premise mostly depends on maintaining the same tempo that got the batsman past the century mark in the first place. This, in a nutshell, was Bradman, and there is nothing fundamentally wrong with that, providing the team’s needs are always at the forefront. For all his many personal faults, as well as his self-absorbed approach to his own batting, nobody could ever accuse him of not wanting to win as much as any player before or since.

Win a Ziggy BBQ for Grand Final day, thanks to Barbeques Galore! Enter Here.

What follows is an extrapolation of Bradman’s highest scores in Ashes cricket into a post-1970 setting regarding over rates as well as Tests restricted to five days. This is not theorising a different approach by Bradman, but rather adopting the exact same approach, with the only dynamic changing being the number of overs bowled in a day. It is not about simulating conditions facilitating a much more even contest between bat and ball pertaining to the greater variety of pitch conditions, not to mention hordes of great bowlers that inhabited Test cricket in the 1970-99 period of play, but, in fact, sticking religiously to the mostly flat pitch conditions and fewer genuinely world-class bowlers around during the 1930s as well as immediately after the war.

The only thing that changes is the imaginary abolition of timeless Tests as well as 20-over hours, replaced by 15-over hours and five-day Tests in both Australia and England. Precisely 50 per cent of Tests Bradman played in were timeless, 49 per cent (25/51) if we adjust for the fact that he didn’t bat in either innings at the Oval in 1938. Pre-WWII tests in England that weren’t Ashes series deciders were four days in length, but bowling overs in the amount of 120-130 per day. Therefore, even a four-day Test in that era contained, assuming four fine days, around 500 overs, whereas a five-day Test in contemporary times will see no more than 440 overs, if we are lucky, with ever increasingly diabolically slow over rates post-2000.

The best example to pre-explain how the extrapolation works is by using Bradman’s 309 in a day at Headingly. A full day’s play in those days would see at least 120 overs bowled, whereas in the modern era the same number of overs would take four sessions. Therefore, all else being equal, Australia reach 3 for 458 with Bradman on the aforementioned 309 not by stumps on Day 1, but that is rather their score line when lunch is taken on Day 2.

Finally, the reason I am not doing non-Ashes Tests is because Australia’s three other oppositions in Bradman’s time were all minnows, and it is much easier for batsmen to rack up colossal individual scores and still achieve a result when playing against weaker batting line-ups, providing you have a reasonably strong attack yourselves – there is no better example of this than Matthew Hayden’s 380.

Enjoy…

(Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

254 at Lord’s 1930

England 425 (128.4 overs)

Australia 6 declared for 729 (232 overs)

There are 49 overs left in Day 2 when Australia’s innings begins. Bradman goes in at 1 for 162 after 66.4 overs, just after the drinks break in the opening session of Day 3. Woodfull is on 76 off 195 balls and there are five extras.

Woodfull is dismissed at 2 for 393 after 135.2 overs, 3.4 overs before stumps (on Day 3). Bradman is on 146 off 216 balls. Bradman and Kippax are dismissed three runs apart and the score is 4 for 585 off 199 overs. Australia lead by 160 at tea on Day 4. Even if Australia declare at this point, England’s second innings of 375 – leaving them 215 ahead – is to last the rest of the match i.e., four sessions.

This is a doomed draw in a post-1970 scenario and there is nothing Australia can do to alter this. Australia remains 0-1 down after two Tests, rather than break back to 1-1.

334 at Headingley 1930

Bradman is 232 not out at stumps on Day 1, and Australia are 2 for 344, rather than 3 for 458. In reply to Australia’s eventual 566, England’s reply of 391 finishes an hour before stumps on Day 4, and, given it is a five-day, rather than four-day match, Australia do not have the option of the follow on. Another doomed draw and Australia are still 0-1 down after three Tests, the fourth is a rain ruined draw, and England keep the Ashes. Can Australia square the series?

Alternate scenario…

Let’s imagine Bradman gives it away on 122, the reason being, this is related to a follow-up article I plan to do on the overall statistical phenomenon that was Bradman. The equivalent of a full day’s playing time, plus another hour on top of that, was lost in the actual match, which means when Australia begin the third innings at 0 for -37, only 39 more overs will be bowled in total. Even if we imagine no time lost at all over the course of the match, which now includes the rest day to make five (days), then when Australia set out at the aforementioned 0 for -37, there remains just a touch less than five full sessions (145 overs including another change of innings between third and fourth), for either side to push for a result, but very unlikely given that, even with Bradman facing 285 less deliveries, the match will still have seen only 20 wickets fall to lunch on Day 4 in almost 300 overs.

232 at The Oval 1930

Australia’s 695 reply to England’s first up 405 finishes a mere hour before stumps on the final day. Even if Australia declare earlier, say, at Archie Jackson’s dismissal (for 73) at 4 for 506, 101 in front, this would occur pretty much right on stumps on Day 4, and still only leaves 90 overs left in the match, which to that point would have produced 911 runs for a mere 14 wickets in four full days of play. England win the series 1-0.

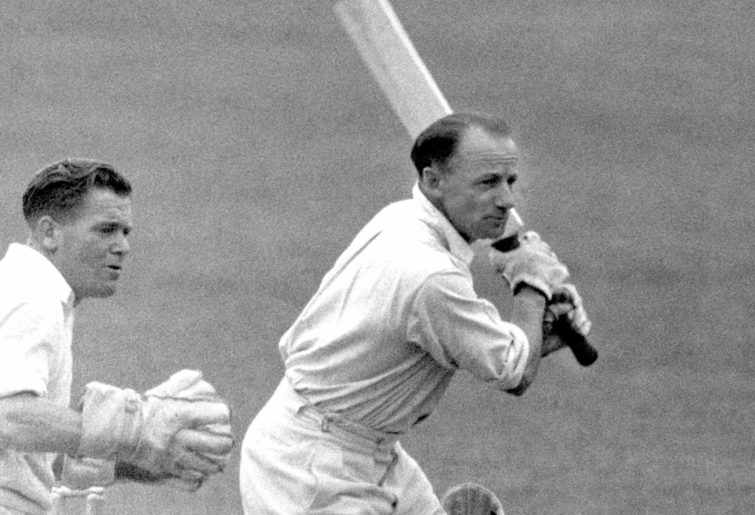

Sir Donald Bradman. (PA Images via Getty Images)

304 at Headingley 1934

I agonised over this one but, at the end of the day, in the modern extrapolation, there will be 18 overs only on the final Day 5, the Tuesday, rather than 24, but four full 90-over days before this, rather than three 120-over days, with no rest day in the middle, on the Sunday.

The starting point is that England batted 136 overs in their second innings for 6-229 and were therefore 16 for 429 overall off a total of 242 overs. It will take another 30 overs for Australia to snare the last four English second innings wickets and at the same run rate they will score another 51. Therefore, Australia will have to make 481 (rather than 584) to break even, but will only have 100 overs to do it. This is not realistic. They can probably make 481 in 130 overs if they push it along a little earlier, but it is difficult to extrapolate how much Bradman will have to give it away on for the good of the team keeping the game moving forward, but 200 might be a conservative estimate.

The bottom line is that in the modern-day extrapolation, the game is on a result trajectory until the severely rain-shortened final day, so it is difficult to lay too much blame at the feet of the Australian captain, Bill Woodfull, regarding declaration. This is, of course, providing they bat no longer than 130 overs (rather than 183) and lift their run-rate from 3.2 to 3.7. This also assumes, naturally, that in a modern-day setting, the emphasis is on actually winning the game, rather than appeasing the crowd that has supposedly mainly come to see Bradman bat.

244 at The Oval 1934

This Test can still have a result, providing Australia enforce the follow on, 380 ahead. In this scenario, the match will come close to finishing by the end of Day 4.

However, England will very likely have hung on for a draw in the first Test as it occupied comfortably more overs than can be bowled in a post-1970 five-day Test, so the series finishes 1-1, and England come away with the Ashes for the fifth successive series, assuming bodyline still occurs in between.

270 in Melbourne 1936-37

In the real events, the equivalent of 127 (eight ball) overs were bowled and there were two changes of innings across the first two days and Australia’s second innings was a mere over or two old, ending with them on 1 for 3 at stumps (on Day 2). With modern (six ball) over rates, the match does not reach this same position until just after lunch on Day 3, which also happens to be the greatly rain-affected pitch which had the opportunity to begin drying out on the Sunday rest day of the time.

In the extrapolation, Australia reach their 5 for 97 roughly an hour from stumps on this alternate Day 3. Does Bradman go in yet, at 5 for +221 as he did in the real events, or does he keep dropping himself down the order, as the pitch will not be properly ready for him to bat on until after lunch the following day, and there is little hope the rest of the team can survive another 45 overs (or so) on such a treacherous surface. In any case, based on overs bowled, scoring rate, and the modern expectation of 15 overs per hour, Australia will be bowled out right on lunch the following day, will double their score in the meantime, with Bradman obviously failing for the second time in the match. Then, England will begin their run chase at pretty much precisely the same point in time that Bradman went in during the real events. With the pitch now dried out into a nice batting surface, which Bradman obviously doesn’t get to bat on in this modern-day extrapolation, England’s target will be virtually the same 323 that they actually managed to total batting last in the real events. Remember also, in the timeless tests on roads of eight (8) years earlier, England had successfully chased 332 for 7 down, while Australia had had the successful chase of 5 for 287, both on this same ground, two Tests apart.

Alternate scenario…

If we still allow the rest day, which didn’t actually permanently go the way of the dodo until the second half of the 1990s, then Bradman gets to actually go in at 6, rather than 7, at the fall of Bill Brown’s wicket with the lead on 198. Fingleton will now join him at 5 for +221 roughly five overs before drinks in the middle session of the day. If Australia want to set a safe buffer of a 400-run target, they will have to bat until 12 overs into the final day, but will then have only 75 (six ball) overs to bowl England out, whereas they needed the equivalent of 105 to do so in the real events.

With extrapolation, Bradman and Fingleton’s partnership will stand on 183 when the futile declaration comes, and Bradman’s own score will only be around half the 270 he had time to make in the real events, with this extrapolation retaining his actual scoring rate that innings of 72 runs per 100 balls faced.

Australia’s Don Bradman batting (Photo by S&G/PA Images via Getty Images)

However, in this rest day scenario, Bradman would certainly be cluey enough, that with the pitch now a fine batting surface, the team’s victory prospects would be much better served by bringing in McCabe ahead of Fingleton. If we assume that McCabe, under the circumstantial deadlines of this particular match, can score at least twice as fast as Fingleton’s strike rate of 31.8, then he and Bradman can push the lead beyond 330 and leave Australia 110 overs to bowl England out a second time. If Bradman gets Rigg to give it away earlier, and even ‘going for it’ for a few extra bonus runs, and the fact that there are still four wickets left if and when Bradman and McCabe are separated, then enough acceleration is theoretically possible to get the lead to 350 and still give themselves those aforementioned 110 overs at England. Bradman will be around 65 not out at the declaration, and Australia’s victory prospects in this extrapolation are genuinely good – unless perhaps England shut up shop completely and focus entirely on survival, taking no risks and forgoing on all meaningful run scoring.

212 in Adelaide 1936-37

The first three innings occupied the equivalent of 419.2 six-ball overs, plus three changes of innings, which means that the 392 ‘chase’ begins with only an hour and a half left to play in the match. What do Australia have to do second time around to actually make a match of it, extrapolated to post-1970 over rates?

Australia’s innings begins at 0 for -42 with nine overs to be bowled at the end of Day 3. Bradman goes to the wicket at 1 for -21, 3.3 overs into the fourth day. It is 3 for +155 when Stan McCabe is dismissed for 55 about half an hour into the final session on Day 4, Bradman is on 86. To bowl England out a second time, Australia’s innings will need to end in another 20 minutes, or five overs, and even then, it will be a close-run thing. Unfortunately, in the equivalent of 98.4 six-ball overs, England were able to score 243. So, this match is also a doomed draw, as per most Tests on the same ground during the 1980s.

144 not out at Trent Bridge 1938

Australia’s 411 reply to England’s 8 for 658 declared finishes a little under half an hour to tea on Day 4. Tea is taken immediately, and there are 35 overs remaining in the day, and then 90 on the final day. They will probably call the game off half an hour early, so Australia’s second innings, following on, only goes for 118 overs, not the 184 in real events. This means that Bradman will only face about half the 379 balls that he faced, and will, therefore, be 72 not out at the end, instead of 144 (not out). Their innings will finish pretty much precisely at the point Bill Brown was dismissed for 133 at 259, a real score of 2 for +12.

102 not out at Lord’s 1938

It seems that about 40-odd minutes of playing time was lost across the first two days (roughly 227 of possible 240 overs bowled), and then only about 53 of 120 overs were possible on third day, followed by 108 of 120 on fourth and final day.

Extrapolated to post-1970 over rates, with the same playing time on those same four days, Australia face only 30, rather than 48.2 overs in the fourth innings, and are 3 for 120, rather than 6 for 204, with Bradman on about 74 off 80 balls, rather than 102 off 135.

If we replace the rest day in between second and third days with a fifth playing day, at modern over rates, Australia have an extra 90 overs to score 195, and if we assume the same slump to the aforementioned 6 for 204, then 71.4 overs remain to score another 111 with only four wickets still standing, with Bradman’s strike rate meanwhile having dropped from 92.5 to 75.6 as wickets have regularly fallen around him. The big unknown is what the weather was like on that rest day between Days 2 and 3 in the real events, and consequently how much play would have been possible had it in fact been the third of five playing days.

Bear in mind also, with time drastically running out, and England needing to win the match more desperately than Australia had to, England still had two (2) wickets left in the shed when their declaration was made, with a supremely talented young batsman named Denis Compton on 76 off only 137 deliveries, so England could quite conceivably have pushed their lead to beyond 350 with still plenty of time then to bowl Australia out, again, depending on what amount of play would have been possible, had the aforementioned rest day mid-Test been a playing day to make a five-day Test with modern over rates.

234 in Sydney 1946-47

As far as I am aware (and I’ll take correspondence on it), the last ever timeless Test was in South Africa in 1939. And yet, this test went into a sixth day. Were Tests in this resumption series post-WWII scheduled for up to six days?

It also appears to have been partially weather interfered, but even if it hadn’t been, it took 500 overs (plus two changes of innings) for Australia to complete their victory – even five fine days in a row, this is more than 10 per cent more overs than can be facilitated in a post-1970 Test match.

In the real events, Bradman and Barnes batting on to 234 each, would have seen England’s second innings (third of match) finish on 2 or 3 wickets down with the total somewhere in the 200-220 range (3 for 220 would be equivalent to 3 for -184). For Australia to win the match under these circumstances, even in a nail-biter, wicket-taking wise, a declaration would have to have been made when Bradman was around 170 (and Barnes around 195).

A more realistic scenario would be to step on the gas a little earlier and utilise the entire line-up to reach the deadline sooner and give themselves comfortably more overs, and this might see Bradman giving it away/perishing on around 150 for the good of the team, with Barnes already having made way on a similar score (or even slightly higher, but obviously at a much slower scoring rate).

138 at Trent Bridge 1948

It appears that about four hours of playing time was lost across the four days, but even without this, the 506 overs bowled, in addition to three changes of innings, is well beyond the capacity of any post-1970 Test match. Assuming the same time lost in a modern extrapolation, England finish the match on around 3 for barely 200 in the 3rd innings, which is the equivalent of 3 for -140 odd.

Generously pretending five full days play, England finish on around 6 for 335 in their second innings when stumps are drawn, which is the equivalent of about 6 for -10. Despite Australia’s class attack, beyond England’s first innings, the first of the match (when they were possibly caught on a sticky), there is little, if anything, in the deck to provide for an even contest between bat and ball to facilitate a result in an extrapolated modern setting.

173 not out at Headingley 1948

It appears as if about two hours of play was lost across the first four days, with around 17 overs (lost) on the opening day of the match. Even had no play been lost, extrapolated to post-1970, England’s second innings finishes within half an hour of the cessation of the fifth and final day, and the match is called off immediately, with Australia not even getting a second innings.

Factoring in the aforementioned lost two hours (across first four days), and assuming they call the match off half an hour before stumps on the final day, England finish (in third innings of the match) on about 4 for 270, in reality 4 for +308ish – there is literally zero scope for them to even make a sporting game of it with any even remotely enterprising declaration.

The Knightwatchmen who say Niihttps://https://ift.tt/9vmksZz Don Bradman’s incredible records might have looked under modern Test conditions

Post a Comment